Valeriy Sokolov

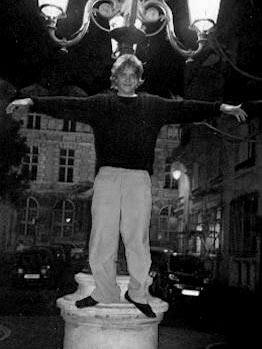

Recital in Toulouse, september 2004

He had tucked his violin under his chin and meticulously but swiftly tuned it. While delicately preparing his bow to come into contact with the G string, he had already imparted his left hand with the discreet vibrato appropriate to the opening of the work he was about to play – Eugène Ysaÿe’s Third Sonata. The first note, enunciated pianissimo but with an extraordinarily pregnant sound, made my spine tingle. And what about the brief paroxystic crescendo culminating on a fortissimo A major sixth that immediately followed, to which succeeded a perfectly-calibrated long-drawn-out silence which paved the way for a lightning shift in tone and texture for the next two notes – an unexpected G natural and F sharp that seemed to loom up from another world? Only thirty seconds had elapsed since the very first note had reached my ears – springing not so much from Valeriy Sokolov’s hands than from his mind and soul – but already I was gripped to the very core of my being. Some eight minutes later, after having placed an explosive final chord, his face, until now aglow with concentration, broke into a smile.

in duo at Montrouge, 2003

It was in Britain, in the spring of 2003, at the Yehudi Menuhin School, that I first had the opportunity to hear Valeriy Sokolov play. I had no more than learned of his existence when he offered to play me the Ysaÿe Sonata. As he did so, not the slightest tension marred the impression he gave of total ease with the instrument, absolute control of technique, a musical maturity which made the fact that he was only sixteen completely irrelevant, and above all an utter abandonment to the flow of the music. I had the same impression when, at my request, he went on to play Bach’s majestic Fugue in A minor for solo violin, and again two days later, when I watched the amateur video he had slipped into my hand of a concert three years earlier in Kharkov with the Ukraine Symphony Orchestra, at which, then aged thirteen, he performed Khatchaturian’s Violin Concerto.

There are today some superb virtuoso violinists. Yet, is there a single one amongst them whose soul’s core – their sound – indisputably bears the stamp of an intensely original art, as did that of the five or six greatest violinists of the century that just ended?

Since the passing of the last among them, I had been asking myself that question, and had not succeeded in coming up with a clear answer. Truth to tell, before this impromptu encounter with Valeriy Sokolov, I did not expect I would hear again such an incandescent sound in my lifetime.

At all events, listening to Valeriy Sokolov launched me into a reflection upon the sad fact that we had no record, combining sound and image, of the early stages of the career of the musicians who had left a profound mark on their era. A compelling thought dawned upon me: I was going to try and capture as soon as I could Valeriy Sokolov in all the freshness of his youth.

The quixotic nature of a project featuring a totally unknown young violinist did not escape me. Who would be interested? Who would be willing to help raise the necessary funding and to provide the complex logistics for such a project I drew up a deliberately modest plan, which aimed simply at organising and filming a recital, to be preceded by a short introduction which would provide the public with a brief biographical presentation of the violinist.

It was not that a fully-fledged documentary film relating the prodigious odyssey of a young Ukrainian originating from a rather deprived land of Eastern Europe, and ending up at the Yehudi Menuhin School, would be devoid of interest. Quite the opposite. At thirteen, Valeriy Sokolov, accompanied by his mother and his teacher, embarked on a coach-journey across Europe to take part in an International competition in Spain; as a result, he was awarded a grant which allowed him to study at the famous school. Sooner or later, I will make a film about that odyssey and the birth of a career.

For the moment, I had at all costs to attend to the realisation of my sole objective : the creation of a musical film which would both meet the immediate requirements of a television programme, and record for posterity the first sparks of a clearly outstanding talent. After numerous hitches and setbacks, I succeeded in obtaining support from my producers, Idéale Audience in Paris, and the television channel Arte. A year later, having spent a long time with Valeriy working out the details of the staging of the project, we started filming.

shooting in Toulouse, september 2004

And here we are now, barely two years since the day I first heard that glorious violin, in a position to offer the viewers this film, which I had dreamed of directing perhaps more than any other, because it seemed fated to elude me.

What does the future hold for such a talent? No-one can say with certainty. A great career depends on many factors which are difficult to gauge in advance. However, there is little doubt in my mind that Valeriy Sokolov ought to become one of the major violinists of our time.

It seems almost superfluous to add that Valeriy is also gifted with unusual charm, spontaneity and ardour. Whatever the future holds in store for him, I am convinced that his radiant personality will come over the screen and win the hearts of all those who watch him playing.

Bruno Monsaingeon. September 22nd, 2005

about « Valeriy Sokolov, Natural born fiddler »

on Valeriy Sokolov :

Valeriy Sokolov, natural born fiddler

Valeriy Sokolov, natural born fiddler Valeriy sokolov interprets sibelius violin concerto

Valeriy sokolov interprets sibelius violin concerto