Glenn Gould

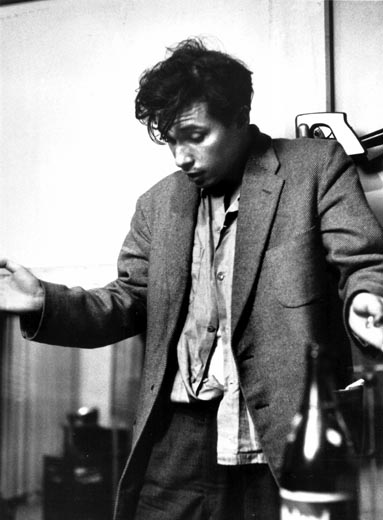

the last puritan, 1958

It all started off with a message in a bottle. In October 1971, I had sent a letter to Glenn Gould, care of CBS Records, New York. In it, I narrated in some detail the circumstances of my encounter with him in Moscow a few years earlier; an encounter in the gouldian sense of the word.

He was not really in Moscow that summer of 1966 when, as a student, and rather broke, I had nonetheless bought up the contents of the one record shop to be found in the city. The round black discs tucked away in their ugly unmarked papier-mâché sleeves cost only one rouble apiece; a sum not large enough to disrupt my scanty wallet. Such was the bargain that I was not going to waste time being selective. Then and there, I purchased all sixty titles lying on the half-empty shelves of the shop’s classical section. I even made a quick jaunt to the adjoining department which, although deserted, presented a much more abundant supply. It offered, for a most democratic thirty kopecks, infinitely more luxuriously packaged records of a political nature. There I acquired a recorded sample of the speeches of the future recipient of the Lenin Prize for literature, and then current ever-present Secretary General of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, comrade Leonid Breshnev.

One would have surmised that it was not this particular recording, hilarious though it was to the ears of a young westerner, upon which I focused my attention. The crinkled label clumsily stuck in the centre of one of the micro-groove records of the collection I had harvested that very afternoon had much more sharply stimulated my curiosity. It featured the name, almost unknown to me, of a performer who played Johann Sebastian Bach’s three-part Sinfonias.

I don’t think I was less inflamed that night than Blaise Pascal during his night of fire . “Joy, joy, tears of joy!!!”

In my letter to the protagonist of that overwhelming encounter, I was too restrained to recount what I am writing here to-day. However, I made it clear that I had heard his calling, while explaining much more prosaically my ideas on the way I would like to make films about music, and more specifically a film with him. I was a musician; but, in matters of cinema, I was just a beginner, and had only limited experience; just a few ideas.

The message in the bottle had been launched into the ocean. It still had to get across the Atlantic and reach its mysterious addressee. Was he ever going to reply? I did not harbour too many illusions.

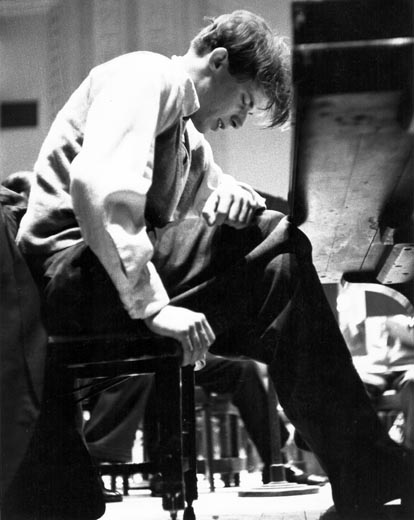

Carnegie Hall, 1959

Six months later, I had his reply. A torrential letter, some twenty pages long, incredibly juvenile and enthusiastic, in which he said he found my ideas intriguing. He no longer travelled, but what about my coming over to Toronto to visit him?

A meeting, not in the gouldian, but in the more banal sense of the word, was therefore going to take place. Nothing so banal ever affected my existence so much.

"Longfellow"

I was quietly practising Brahms’ second violin sonata when, towards 2 o’clock of the afternoon, he knocked at the door of the hotel room he had booked for me. Thereafter, whether in the summer or in the autumn, I never saw him rigged-out differently, whenever he ventured outside. That month of July 1972 was scorching. Yet, neither his huge overcoat, nor the scarves and snow-boots he was wearing, nor indeed the strange way he held out his hand to retract it as soon as it had made contact with the tips of his interlocutor’s fingers, impressed me as much as that first conversation in the flesh. Before I came to Toronto, we had exchanged a good many letters and talked at length on the telephone. He always seemed to have plenty of time. However, only at 8 o’clock the next morning when he left my hotel, did I realise that eighteen hours of uninterrupted conversation had elapsed since he had crossed the threshold.

Three days later, after treating me to a lavish private recital ( close to six hours of music by Schoenberg, Hindemith, Strauss and Schubert – not the sonatas, or the Impromptus, but the 5th symphony!) in the recording studio where he stored his piano, he drove me back to the airport, and took his leave by saying: “I will feel very comfortable making the films with you”.

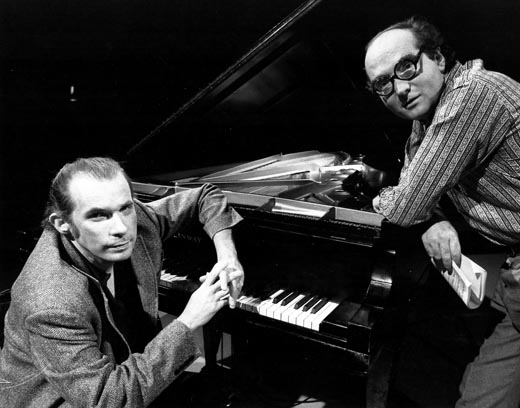

filming the Goldberg Variations - New York, 1981

Copyright KIPA, Patrick Guis

Indeed, all those hours of conversation had not been idle ; we had worked blithely, so that the first outline of a scenario for the film we wished to shoot was ready.

I still had to persuade those in charge of the Music Department of the French national television network to support this endeavour. No small fare! Here I was with no standing proposing to make a film about an “obscure” Canadian pianist! As incredible as this may sound, such was alas the level of Gould’s notoriety in the musically provincial France of those days. During the nine years of his prodigious public career, Glenn had never set foot, let alone performed, in that country. And although some of his recordings had indeed been released – and savagely criticized – on French territory, they had been deleted donkeys’ years ago, including that of the Goldberg Variations. After all, I had had to travel to Moscow to be exposed for the first time to one of Glenn’s recordings, the remaining part of which I could only hope to dig up at the flea market. Other European countries fared hardly better. True, a few recordings were to be found in Germany, a country that had acclaimed Gould three years in a row. But not in the British Isles, although England was considered the Mecca of musical life in Europe. Gould had given four concerto evenings in London back in 1959, yet England, though appreciative of eccentricity, had not sensed the profound originality of this artist native of her overseas colonies. They had not taken him really seriously.

with the Detroit orchestra conducted by Paul Paray

In any event, at the time, the concept of an international co-production did not exist in French television. In spite of the odds, I managed to get the whole process underway in a little over a year; a year that Glenn and I put to good use in order to rework, reformat and refine our scenario, both via correspondence and another visit to Toronto. It was an ambitious project which consisted of making a two and a half hour long film. Originally, we had considered dividing it into three parts, then eventually settled on four, one of which we chose to make in the style of a feature film rather than a documentary, in the sense that we were less interested in raw reality than in its reconstruction. For the second instalment, in which we had decided to stage a recording session, we went so far as to define which wrong note Glenn would force himself to play in the Bourrée of Bach’s 1st English Suite, so as to make that sequence plausible. Poor Glenn; he who was so allergic to wrong notes! During the shooting, he had to play that same wrong note over and over again conscientiously for each new take.

filming "The Question of instrument" - Toronto, november 1979

On the other hand, contrary to what has been written here and there, our dialogues were not scripted. They were improvised and completely spontaneous, all the while following a carefully thought-out dramatic sequence. Every take was to have a different verbal content. We would leave it up to the editing process to reconcile improvisation and preconception.

Once we had set a date to carry out the filming in September 1973, all the necessary elements of logistical support were put into motion. I was already in the plane, a few days ahead of the numerous Paris-based technical crew which was to join me in Toronto, when Glenn tried to contact me by telephone to request that we postpone the shooting. A sudden shoulder pain prevented him temporarily from playing the piano. I was dismayed, but was immediately comforted when I saw with what energy Glenn applied himself from his den to retaining the various studios which we had contracted at the outset of the project. I returned to Paris sheepishly nonetheless. It was a field day for the television bureaucracy. Never having been convinced of the merits of my costly and, in their eyes, dubious project with that whimsical pianist, they rejoiced. The postponement made the project more expensive, which they used as an excuse to try to torpedo it. We miraculously were able to overcome their ill-will, and set a new timetable for the beginning of the following year.

Glenn Gould the Alchemist - Toronto, february 1974

Everybody was ecstatic during the shooting which took place in January and February of 1974. It took the balance of the year to complete the editing. I constantly kept Glenn informed of our progress by mail and by telephone. During the course of these exchanges, while inquiring whether my new project of filming the 48 Preludes end Fugues of Bach’s Well tempered Clavier with him managed to gain approval in the appropriate quarters, Glenn wrote to me “these weeks remain among the happiest of my professional life “.

Glenn Gould the Alchemist - Toronto, february 1974

The broadcasting of this film, whose counter-subject was the relationship between music, the techniques of recording and mass communication, and in which Gould played Bach, Schoenberg, Byrd, Gibbons, Wagner, Scriabin, Berg and Webern, had enormous resonance in France. The intellectual world, even more than the musical circles, emoted. In a country where he was practically unknown the prior day, Glenn Gould had become overnight, without any physical presence, a veritable myth.

Webern's Konzert working score by Glenn Gould - collection B.M.

Truth be told, we benefited from a bit of incredibly good luck. The day the first instalment was to be broadcast on one of the three channels of French television, the TV workers went on strike. However, by law the screens on the three channels were not permitted to go blank. They had to carry at least one programme simultaneously. It was a Saturday evening, traditionally devoted to live variety shows. The strike made live broadcasting impossible, so the programmers, no doubt with heavy hearts, had to fall back on the only film planned for later that evening; which they ended up showing in prime time. All those Saturday night television addicts who could not stand being deprived of their drug had no choice but to watch the weird character who spoke of his decrepit chair as if it were his best friend; who jubilantly proclaimed his faith “in the intrusion of technology, which imposes upon art a moral dimension that transcends the idea of art itself”; and who played Bach and Wagner in an ecstatic trance.

Twenty eight years have gone by since. Glenn is no longer physically of this world - indeed was he ever? It does not seem that the extraordinarily spontaneous Gould who reveals himself here has lost any of his magic.

Bruno Monsaingeon. October 4th 2002

on Glenn Gould :

-

Glenn Gould, the Alchemist

Glenn Gould, the Alchemist

99' Date: 1974

EMI collection classic archive ™ -

Glenn Gould, hereafter

Glenn Gould, hereafter

French title: Glenn Gould, au-delà du temps

106' Date: 2006

EuroArts / Naxos

- edited in Blue-Ray -  Le dernier puritain

Le dernier puritain

Glenn Gould writings, vol.1

éditions Fayard, 1983 Contrepoint à la ligne

Contrepoint à la ligne

Glenn Gould writings, vol.2

éditions Fayard, 1985 Non, je ne suis pas du tout un excentrique

Non, je ne suis pas du tout un excentrique

éditions Fayard, 1986 Glenn Gould : Chronicle of a crisis

Glenn Gould : Chronicle of a crisis

followed by Concert correspondance

éditions Fayard, 2002 Chemins de traverse, Glenn Gould

Chemins de traverse, Glenn Gould

éditions Fayard, 2012