Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

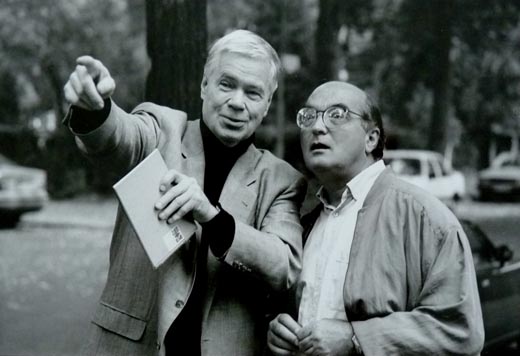

Berlin, 1994 - photo M. Weiss

December 1993. For a few days, at his home in Berlin, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and I have been going through a number of audio-visual documents of which he detains a videocassette copy. Late in the evening, he has been showing me a television programme on Brahms' "Die schöne Magelone" in which he appears in a double capacity, singing the fifteen Romances of the "remarkable love-story of the beautiful Magelone and Count Peter from Provence", and narrating the story. The performance of the actor - his spoken voice, its inflexions and its rythm - are just as compelling as that of the singer. As an encore, he performs "Feldeinsamkeit", one of the songs from Brahms' opus 86. His interpretation is of such supreme beauty that I find it difficult to contain some sudden tingling in my lachrymal system. I mumble a few conventional words meant at expressing as well as at disguising my emotion. Not being the kind of man who pours out his feelings without control, he interrupts my mumbling:

- "There wasn't enough "legato"; I should have stopped earlier".

Exactly one year ago, he put an end to his career as a singer, right after a Gala concert at the Münich Opera on December 31st 1992. He says to me he took that decision during the night that followed. An abrupt, final, irrevocable decision.

Performers who have left on a particular musical score an imprint that is so strong that it forever seems to belong to them, are very rare indeed. One thinks of Glenn Gould and the "Goldberg Variations", of Maria Callas' "Tosca", of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf's "Fiordiligi", of Yehudi Menuhin and Bartok's 2nd violin concerto, of Dinu Lipati and Bach's 1st Partita. In Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau's case, the identification has to do with the whole vast realm of the German Lied, the innermost recesses of which he has explored. A field that one cannot even mention without making a reference to him, for generations to come. Lieder, he has recorded by the thousands, as well as French, Scandinavian and Russian songs; along with these, he has also sung nearly a hundred Opera parts from all epochs, and countless Cantatas and Oratorios. In the course of an exceptionally long and carefully managed career, he has, in other words, alternated with equal success the widest possible variety of genres.

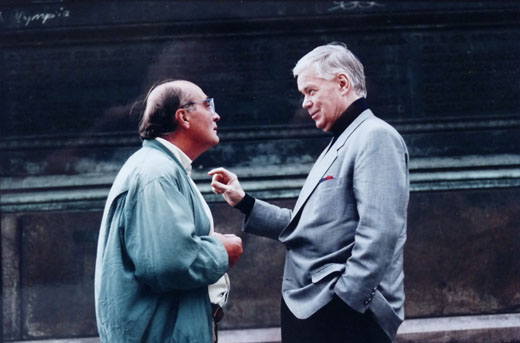

Berlin, 1994 - photo M. Weiss

He was said to be difficult, secretive, almost shy and unapproachable, but these are obstacles that stimulate rather than discourage me. Yet, on the occasion of our first professional meeting, I found a man who was indeed reserved, but openly and joyously prepared to talk in detail about the project I had come to submit to him. Considering the dimension of his personality, it could not be anything less than a large-scale project, which would keep us busy for several years during which we would certainly have the leisure to "tame" one another. My ultimate purpose was, naturally, to conceive and produce a monumental filmed profile - the object of the present release - a wide-ranging retrospective of the singer's career, which would give a glimpse of this great artist's enormous accomplishments throughout his life.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is an essentially earnest artist, a man eager to protect his work and his privacy, and therefore rather reluctantly disposed towards the shallow and uncouth forms of expression of television. The recorded legacy of the most prolific singer of our time is gigantic - a sizeable book would be necessary simply to provide a detailed list of his recordings - yet, curiously enough, and probably because of his strong dislike of the unwieldy logistics of the cinematographic process, there are relatively few filmed or televised programmes documenting his interpretations. At the time when we began working together, the question of a possible retirement from the stage had not yet overtly been raised, and the voice I was hearing seemed to me never to have been so ductile and stirring ; it was as though the master of this voice, by dint of a passionately renewed perusal of the great texts which had accompanied his life, was rediscovering the kind of primeval spontaneity that lies behind the highest stages of intelligent premeditation. From now on, he no longer offered these great texts to our ardent listening , he incarnated them.

The research of documents which we had already undertaken had led to the detection of treasures, together with many items of dismaying cinematographic banality, or gems of frustrating brevity; it had also allowed us to carry out an almost complete analysis of the most blatant gaps in the existing filmed repertoire of our hero. Consequently, it was decided that we should, in the next few years, start out by trying to fill in those gaps and film some of the major opuses of Fischer-Dieskau's repertoire. To that effect, we organised recitals of Schumann and Schubert songs at the Nürnberg Opera, Masterclasses devoted to the same authors, in Berlin, as well as a "Schöne Müllerin" in Paris (which was to be, in April 1992, the last public appearance of the great German baritone in that city).

Once we had defined these programmes, with the underlying idea of letting them have their own independent existence, but also of providing us with a substance on which we would draw in order to make the portrait of the singer, I needed to give a little bit of thought to the way I would film song recitals. Whereas the mechanical, and occasionally heroic, aspect of instrumental performance can be the object of a visually fascinating transposition, there is in the voice something which goes beyond the purely instrumental, and that is the emotional involvement which springs from singing and irradiates the singer's features. My approach would obviously have to take that into account; if one sought to catch a powerful expression more than anything else, the connections between shots, and the rythm in which they alternated had to be made almost imperceptible and slow. Moreover, while there is a conspicuous sense of complicity between the singer and his accompanist, the natural position of the one in relation to the other is not exactly ideal for the camera, because of the various impediments brought about by the structure of most concert halls, and by the presence of an audience. Resorting to long dissolves can, to a certain extent, solve the difficult question of defining adequately subtle angles, of finding suitably expressive shots. However, I was also intent on experimenting with a method which, I thought, would yield riveting results. On the occasion of a Schubert recital, we filmed one and a half hour of music in one single sequence shot. Strangely enough, this was a way of addressing the question of the rapport between singer and accompanist: keeping a close-up shot of the camera on the singer's face, during the piano postlude at the end of a song, can be more eloquent in terms of that relationship, than cutting to a shot of the piano, thereby inevitably breaking the emotional continuity of the work. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is not only a singer, but also a phenomenal actor; while the piano alone brings a song to its conclusion, his most minute motions - be it a simple shudder of his eye-brow, or the closing of his eyes - accurately reflect the harmonic structure, the exact rythmic and emotional mood of the music. One can feel his intense presence while he interprets silence. A camera which rejects distraction can then capture a moment of magic.

At the beginning of January 1993, I received a brief letter from Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau: "The hour of a sad truth has come: from this day, I finish my appearances, public courses and recording sessions. As you can think, this is no easy resolution. But after 45 years of uninterrupted work, I may well obey this categorical imperative".

The most sumptuous singer of our century had imposed silence on his song. It was now time to discover the man behind the tremendous artist; the present portrait was filmed during the two years that followed. By drawing on what I had already filmed, on what was still to be filmed (concerts and rehearsals as a conductor, masterclasses, working sessions with his wife, the exquisite and ardent Julia Varady), and on additional archival material which I still had to find, I set out to explore the story of a dazzling career, embodied in that radiantly youthful man. Across all genres, this exploration would lead us all the way to the golden sunset glow of Schubert's "Abendrot" with which I intended to conclude my film. Mere facial resemblance was not going to be my sole aim, as is the case with some painters; a portrait must seize something more: the spiritual magnetism that comes from within.

Bruno Monsaingeon.

about « Autumn Journey »

on Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau :

-

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau - Blu-ray edition

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau - Blu-ray edition

De luxe edition (31cm x 31cm x 2,9cm)

Release: september 2013

EuroArts / Ideale Audience -

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau - DVD edition

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau - DVD edition

De luxe edition (31cm x 31cm x 2,9cm)

Release: september 2013

EuroArts / Ideale Audience -

Autumn journey

Autumn journey

French title: La voix de l'âme

106' Date: 1995

Warner / NVC Arts - unavailable - -

Die schöne Müllerin

Die schöne Müllerin

By Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Christoph Eschenbach

68' Date: 1991

EMI collection classic archive ™ -

Death and the Maiden

Death and the Maiden

French title: La jeune fille et la mort

With the Alban Berg Quartet + the Artemis Quartet, Julia Varady and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

58' Date: 1996

EMI classics