Grigori Sokolov

at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées - Paris, 2002

A dim light picks out the outlines of the hall. Suddenly a massive shadow appears and moves swiftly over to the keyboard, the only brightly lit surface to stand out from the large coffin-like box in the center of the stage. There follows the vaguest of unsmiling acknowledgments in the general direction of the audience, and then the music begins. Throughout the next two hours this music will keep its listeners enthralled with its extraordinary intensity as the audience senses the formidable physical, pianistic, musical and emotional presence of this most secretive of present-day pianists, Grigory Sokolov.

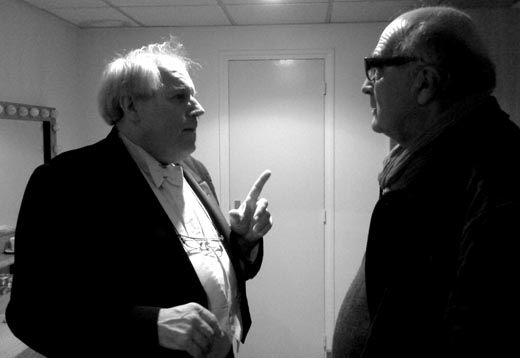

Secretive, he certainly is. A man of vast culture, cheerful and even mischievous offstage, he seems to be cocooned within his own irrefutable logic. Only his musical thoughts are susceptible of being imparted to the public, thoughts embodied beneath his fingers with the utmost interiority and within the ephemeral and exclusive framework of the concert hall. All other considerations, including those of career and self-promotion, are rejected as external to the music. They are, strictly speaking, irrelevant.

The phenomenon of the artist retiring behind his art is both intriguing and salutary. It no doubt accounts partly to the fact that Sokolov is still relatively unknown to the public at large. Yet there are many people who are convinced that, following the deaths of musicians like Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Glenn Gould and Sviatoslav Richter, he is now the greatest living pianist.

In the course of a career lasting almost forty years, starting with his victory at the age of sixteen in the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1966, followed by recordings of The Art of Fugue and one of the Bach partitas, Sokolov has built up a repertory both vast and original: Mozart and Chopin, Brahms and Rachmaninov, Schubert Beethoven, Haydn and Prokofiev often rub shoulders at his recitals with the English virginalists, works by Bach, the French clavecinistes Couperin and Rameau and pieces by Froberger. These works are tirelessly rethought, as we know from the fact that Sokolov gives only one programme in the course of each season of concerts, repeating it as many times as he appears in public. At the start of the season, the works that had constituted one part of the previous season's programme are dropped, of not permanently, at least for a number of years, while their place is taken by a substantial programme of new pieces. All that remains of this activity, apart from the memories of thousand of listeners who fell under its spell, are relatively meagre traces, consisting for the most part of pirate recordings that music lovers throughout the world passionately exchange with each other.

Sokolov has never allowed more than a handful of his recordings to be released. A1l of them are live recordings, as the very principles of studio recording and editing are anathema to his way of thinking. The record company which has him under contract nonetheless continues to tape a large number of the seventy-odd recitals that he gives year in, year out, even though their request to release them almost always comes up against the same negative response, albeit tempered by the phrase ''You can release whatever you want after my death''; he even suggested that his original recording company, Opus 111 (a reference to Beethoven's last sonata), change its name to ''Opus posthume'', a label which seemed to him to reflect perfectly his own ideas on the subject of record releases.

Sokolov himself believe that the concert represents the focal point of magical life and that everything else is artificial. As a result, he is not only reluctant to be recorded but also to be filmed.

In spite of this, we were able to overcome his reservations (In this point of principle, at least on condition that we accept his drastic demands, though the latter were never explicitly stated. The idea of filming a public recital that he was to give at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris on 4 November 2002 was accepted, provided that it was made live, with no retakes and with nothing to detract from his total concentration, which was directed solely at the music. In particular, this meant avoiding the perceptible presence of microphones, lights and cameras.

The programme featured three of Beethoven’s sonatas: Op.14 Nos.1 and 2, followed by Op. 28, the “Pastoral”. All three were played without a break, then came six dances by the Armenian composer Komitas Vardapet (1869-1935) and finally Prokofiev's scintillating Seventh Sonata. In Sokolov’s stupendous reading, this last piece acquired a power such that the bowels of the earth seemed to open up before the listener and in itself was enough to justify the presence of the cameras. After a year of loyal service, Sokolov has now dropped this piece from his repertory in keeping with the immutable plan outlined earlier.

In circumstances such as these, the film-maker can play no more than a modest role, his aim being limited to an attempt to render perceptible, without artifice, the inner world of a great musician who no longer seems concerned with the mechanical vicissitudes of his instrument, so much is he in control of it. Without offering a full account of the shooting script, which was worked out in minute detail in advance, I should nonetheless like to draw attention to one or two fundamental options that I retained. One example will serve for many: the obsessional rhythm of the final movement of Prokofiev's Seventh Sonata (a toccata marked Precipitato by the composer) could lend itself marvelously well to a sequence made up of a large number of very brief shots which, as such, might also have had the advantage of providing a contrast with the series of longer shots used in the same sonata's first two movements. But, on mature reflection, I realized that the extraordinary cumulative effect that was clearly intended by Prokofiev and that is phenomenally well captured by Sokolov would be lessened by this. And so I abandoned this idea in favour of a single shot, which, in my own opinion, is better suited to inducting in us the state, close to hypnosis, towards which this spellbinding music draws us.

The same is true of Couperin’s Le Tic-Toc-Choc that Sokolov plays as an encore. Here three shots would suffice: a wide shot intended to suggest the ambience at the end of the concert, followed by a close-up starting with the second statement of the theme and focusing on the balletic movement of the pianist’s hands, and then a final shot of the concluding chord allowing us to wake, as though unconsciously, from the dream into which strolls has transported us.

In doing this, I hope that, thanks to the evocative power of the images that try to follow the reality of the score as closely as possible and thanks also to a shooting structure largely dictated by the richness of the pianist’s incomparable phrasing, I may have helped the listener and viewer to participate, over and above the interpretation, in the music itself.

Bruno Monsaingeon. August 2003 - Translation Stewart Spencer

about « Grigory Sokolov Live in Paris »

-

Grigori Sokolov Recital

Grigori Sokolov Recital

126' Date : 2002

EuroArts / Naxos -

Grigory Sokolov Recital at Roque d'Anthéron

Grigory Sokolov Recital at Roque d'Anthéron

163' Date: 2016

EuroArts / Idéale Audience -

Grigory Sokolov Live at the Berlin Philharmonie

Grigory Sokolov Live at the Berlin Philharmonie

144' Date: 2016

Deutsche Grammophon / Idéale Audience